Political Campaign Financing: Understanding the Truth About Money in Politics

The evolution of political spending in America

Money has foresight been a drive force in American politics. From the earliest days of the republic, candidates and parties have sought financial support to fund campaigns and spread their messages. Yet, the scale and nature of political spending have transformed dramatically over time.

The relationship between money and politics remain one of the virtually contentious aspects of our democratic system. Critics argue that excessive campaign spending corrupt the political process, while defenders maintain that political donations represent a form of protect speech and civic participation.

Campaign finance laws: a complex framework

The regulation of political spending in the United States operate under a patchwork of federal and state laws, court decisions, and regulatory guidelines. Several key pieces of legislation have shaped the current landscape:

The federal election campaign act (fFEMA)of 1971 establish disclosure requirements for federal campaigns, political parties, and political action committees ( (cPACs)t too to create federal election commission ( fec( FEC)force campaign finance regulations.

The bipartisan campaign reform act (bbra))f 2002, normally know as mccMcCainiFeingoldan national political parties from raise or spend ” ” t money ” (” nds not subject to federal limits ) an)restrict certain types of political advertising.

Nevertheless, the supreme court’s landmark

Citizens united v. FEC

Decision in 2010 essentially alter the campaign finance landscape by rule that the government can not restrict independent political expenditures by corporations, associations, or labor unions. This decision pave the way for the creation of super PACs, which can raise unlimited sums from corporations, unions, and individuals to advocate for or against political candidates.

Types of political spending

Political spending take various forms, each with different regulatory frameworks and implications:

Direct campaign contributions

Individual donors can contribute direct to candidates’ campaigns, but these contributions are subject to strict limits. Presently, individuals can donate up to $3,300 per election to a federal candidate, with primary and general elections count individually. These limits are index for inflation and update every election cycle.

Candidates must disclose the identity of donors who contribute more than $200, create a level of transparency for direct campaign contributions. Political parties and traditional pPACsbesides face contribution limits.

Source: wallstreetoasis.com

Independent expenditures

Independent expenditures represent spending by individuals or groups not coordinate with a candidate’s campaign. Follow

Citizens unite

, corporations and unions can make unlimited independent expenditures to support or oppose political candidates.

Super PACs are political committees that make only independent expenditures. Unlike traditional PACs, super PACs can accept unlimited contributions from individuals, corporations, and unions, though they must disclose their donors.

Dark money

” dDarkmoney ” efer to political spending by nonprofit organizations ( (incipally 501(c)(4 ) )cial welfare organizations and 501(c)(6 ) b)iness leagues ) th) are not requirrequireddisclosingr donors. These groups can spend money on political activities equally farseeing as politics is not their primary purpose.

The lack of disclosure requirements for these organizations has raise concerns about transparency and accountability in the political process. Critics argue that dark money allow wealthy donors to influence elections anonymously, while supporters contend that donor privacy protect individuals from potential harassment.

The true impact of money in politics

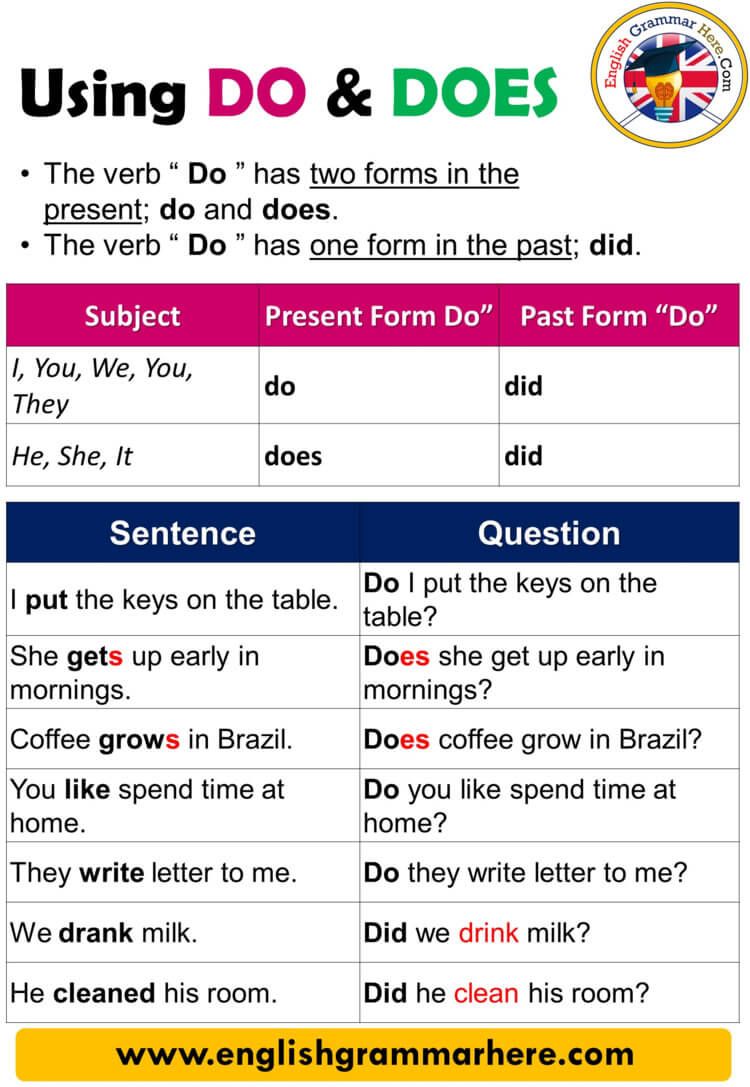

Does money determine electoral outcomes?

One of the virtually persistent questions about political spending is whether it forthwith influence election results. The evidence present a nuanced picture.

While the candidate who spend more money oftentimes win, this correlation doesn’t inevitably indicate causation. Viable candidates typically attract more donations, create a chicken and egg scenario. Furthermore, high profile races with astronomical spending sometimes result in upsets, demonstrate that money entirely doesn’t guarantee electoral success.

Research suggest that political spending has diminished returns. Initial spending help candidates establish name recognition and communicate their message, but additional spending face decrease effectiveness, especially in high information environments.

Access and influence

Possibly the nearly significant impact of money in politics involve access and influence kinda than direct vote buying. Large donors and bundlers oftentimes gain privileged access to elect officials, create opportunities to shape policy discussions and priorities.

Source: srading.com

Studies have shown that legislators’ voting patterns more nearly align with the preferences of their donors than with those of their non donating constituents. This alignment raise concerns about whether elect officials are genuinelyrepresentedt all their constituents or principally those who fund their campaigns.

The potential for quid pro quo corruption — or fifty its appearance — undermines public trust in government institutions. Yet, prove direct exchanges of money for specific policy outcomes remain challenging, as influence oftentimes operate in subtler ways.

Candidate selection and representation

The high cost of political campaigns create barriers to entry for potential candidates without personal wealth or fundraising networks. This dynamic can limit the diversity of candidates and perspectives in our political system.

The need to fundraise besides consume a significant portion of elect officials’ time. Members of congress reportedly spend 30 70 % of their time on fundraising activities, reduce the time available for legislative work, constituent services, and thoughtful policy development.

Public financing: an alternative approach

Public financing systems provide government funds to candidates who agree to limit their spending and private fundraising. These programs aim to reduce the influence of private money in politics and expand the pool of viable candidates.

Several states and municipalities have implemented public financing systems with varying structures:

- Matching funds programs multiply small dollar contributions with public money, incentivize candidates to seek broad grassroots support.

- Clean elections programs provide a lump sum to qualifying candidates who demonstrate community support by collect a specified number of small contributions.

- Voucher programs give voters public funds to donate to candidates of their choice, democratize the campaign finance process.

Evidence from jurisdictions with public financing suggest these programs can increase candidate diversity, reduce the time spend fundraising, and diminish the influence of large donors and special interests.

Digital transformation of political spending

The digital revolution has transformed political spending, create new opportunities and challenges. Campaigns progressively allocate resources to digital advertising, data analytics, and social media strategies.

Online fundraising platforms like act blue andwingedd havedemocratizede political giving by make it easier for campaigns to collect small dollar donations. This shift haempowereder grassroots donors and reduced candidates’ reliance on large contributors in some cases.

Yet, digital campaign tactics too raise concerns about microtargeting, disinformation, and foreign interference. The rapid evolution of digital campaigning has outpaced regulatory frameworks, create potential loopholes and enforcement challenges.

Lobby: the other side of political spending

While campaign contributions receive significant attention, lobbying represent another crucial avenue for money to influence politics. Corporations, industry associations, and interest groups spend billions yearly on lobbying activities to shape legislation and regulation.

Lobbying provide valuable expertise and information to lawmakers but besides create potential imbalances in representation. Substantially fund interests can maintain a constant presence in legislative discussions, while groups with fewer resources struggle to have their voices hear.

The” revolving door ” etween government and the private sector far complicate the lobby landscape. Former officials oftentimes leverage their connections and insider knowledge when they become lobbyists, raise questions about conflicts of interest and undue influence.

Disclosure and transparency

Transparency represent one area of relative consensus in the contentious debate over money in politics. Disclosure requirements allow voters to understand whose fund campaigns and political messages, enable more informed decisions.

Current disclosure laws require candidate committees, party committees, and PACs to report their donors to the FEC, which make this information publically available. Notwithstanding, significant gaps remain, peculiarly regard dark money groups and certain types of digital advertising.

Efforts to enhance disclosure include the proposal disclose act, which would require organizations spend money on elections to reveal their donors, and state level initiatives to increase transparency in political spending.

International comparisons

The United States stands isolated from many other democracies in its approach to political spending. Virtually developed democracies place stricter limits on campaign contributions and expenditures, provide more extensive public financing, and impose shorter campaign periods.

For example, Canada cap individual contributions at roughly $1,500 per year to each party and provide tax credits for political donations. The uUnited Kingdomprohibits pay political advertising on television and radio, importantly reduce campaign costs.

These international models offer potential alternatives to the American system, though constitutional differences — peculiarly the robust protection of political speech under the first amendment — create unique constraints in the U.S. context.

The future of political spending

The landscape of political spending continues to evolve in response to technological innovations, court decisions, and change public attitudes. Several trends and proposals may shape the future:

Small dollar fundraising has gain momentum, with candidates progressively emphasize grassroots support. This shift could potentially reduce the influence of large donors and special interests.

Constitutional amendments have been proposed to overturn

Citizens unite

And establish that corporations do not have the same first amendment rights as individuals. Notwithstanding, the high bar for amend the constitution make this approach challenge.

Technological solutions like blockchain could potentially enhance transparency and enforcement in campaign finance, though these applications remain mostly theoretical.

Conclusion: what’s true about political spending?

Thus, what’s true about spending in politics? Several key facts stand out:

Political spending has increase dramatically in recent decades, with federal elections nowadays routinely cost billions of dollars.

The regulatory framework for political spending has been importantly shaped by supreme court decisions that haveequatede money with speech and extend first amendment protections to corporate political spending.

While money play a crucial role in politics, its impact is complex and not invariably deterministic. Money provide advantages in elections but doesn’t guarantee victory.

The nearly significant effects of money in politics may involve access and agenda setting kinda than direct vote buying or explicit corruption.

Alternative systems, include various forms of public financing, have show promise in reduce the influence of private money and expand political participation.

Finally, the relationship between money and politics reflect broader tensions in democratic governance — between equality and liberty, transparency and privacy, regulation and free expression. Find the right balance require ongoing democratic deliberation and civic engagement from an informed citizenry.

MORE FROM dealhole.com